This post was written by Eleanor Sarpong, Deputy Director and Policy Lead, A4AI.

At this year’s Mobile World Congress (MWC) in Barcelona the buzzword on everybody’s lips was 5G. It was impossible not to be seduced by the many ideas powered by 5G technology on display. I watched a demonstration from the Catalan Ambulance service showing the possibilities of real-time surgery performed by operating staff with guidance from a remote consultant. I saw water filtration systems, smart beekeeping tools, impressive cars and an array of Internet of Things (IoT) gadgets — all using 5G technology in innovative ways.

While 5G promises to revolutionise the way humans interact with each other and the things around them, much of the world is yet to experience the most basic digital technologies. As we celebrate 30 years of the World Wide Web, almost half of the world’s population is still not online. As MWC attendees experience the potential of 5G, in some countries the most basic data packages remain wildly expensive. Our research finds that, across Africa, the average cost of 1GB data is 8% of average monthly income.

So, what does 5G mean for developing regions with large unconnected populations who arguably have most to gain from digital technology? Should policymakers be focusing their energies on 5G to resolve current connectivity gap or is it a distraction from providing basic internet infrastructure and supporting existing technologies for access?

What is 5G anyway?

5G — or 5th generation — is an advanced low-latency mobile technology, capable of processing data more quickly and with greater capacity than previous ‘G’ technologies. 2G gave consumers access to voice calls and basic text. 3G drove the growth of video services like YouTube. And 4G made services such as Netflix, Spotify and a host of other data-heavy applications possible.

5G is anticipated to be a dramatic leap forward, with speeds of up-to 100Mbps opening a new world of digital possibilities. This will not only enable a new generation of consumer and industrial applications, but could encourage an explosion of machine-to-machine communication.

Can 5G close the widening digital divide?

Who is best positioned to benefit from 5G? For the most part, it will be people who already enjoy widespread, low-cost connectivity and affordable access — i.e. those who live in countries that meet the UN’s “1 for 2” affordability target. In many lower and middle-income countries, 3G continues to be the predominant technology with weak uptake of 4G. The many barriers to internet access and quality of service in developing regions means unless there is an effort to develop the ICT infrastructures in those countries with low rates of connectivity, 5G could simply exacerbate existing digital inequalities.

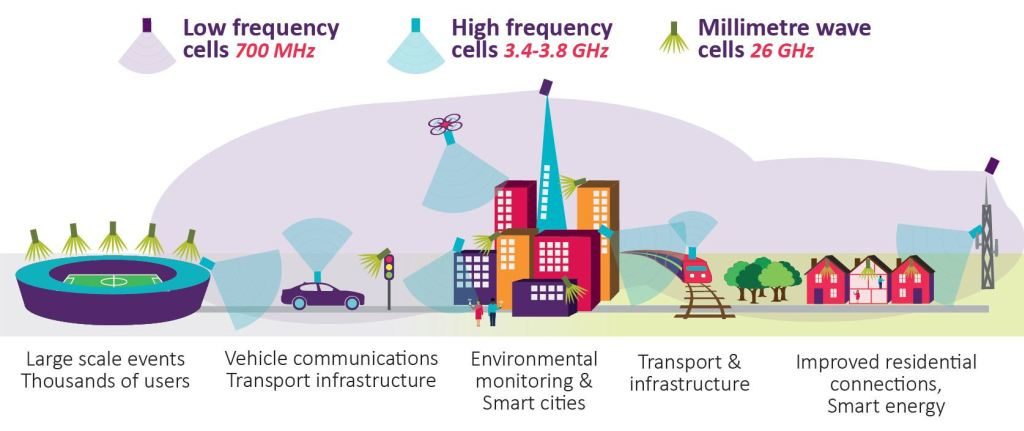

Some have argued that 5G will act as a ‘leapfrog’ technology, allowing countries to fast-track digital development in rural areas. However, these assertions are typically based on tests conducted in low-frequency bands (below 800 MHz) that have wide coverage capabilities suitable for sparsely connected communities. These bands are suitable for internet of things (IoT) technologies over vast geographical areas such as automated transport or drone technologies. However, the actual use cases will determine the real outcome of these tests. Data-heavy 5G applications typically discussed demand higher frequencies (above 3.5 GHz) which support high data speeds. These, though, have narrower coverage. Investment to build 5G infrastructure is most likely to happen in urban areas with sufficient population density to provide a return on investment as shown in image 1, not the rural areas that are commonly underserved.

What investment is needed?

The rollout of 5G technology will demand significant investment in infrastructure, including in new towers capable of providing more capacity, and bigger data centres running on efficient energy. These need to be paired with more fibre deployment and new last mile connectivity solutions to make sure people are able to access this faster, better quality network. There are a number of key steps developing countries can take to encourage network development generally, including:

- Addressing existing bureaucratic challenges around site and fibre deployment and encouraging infrastructure sharing to encourage capital expenditure and to reduce the cost of upgrades.

- Resist prohibitively high spectrum prices and improve spectrum management.

- Couple infrastructure development with investment in skills, relevant content and meaningful use so that end users can actively contribute content and participate in the digital economy.

5G has many people excited. But policymakers, particularly in developing countries, must not let the buzz around 5G distract them from solving existing challenges and building out the foundations of their digital markets. Ultimately, they should aim to eliminate hurdles that increase the digital divide rather than fixate on specific types of technology. Once governments have supportive policy and regulatory environments in place, innovation will happen. They should start by doing the following:

- Establish a forward-looking national broadband strategy. These must be comprehensive plans and strategy that show the country is working to stimulate investment in infrastructure, particularly underserved areas. They should focus on spurring innovation, digital literacy, relevant content and skills to support development. Additionally, broadband policies must be gender-responsive to help close the digital gender gap. Such strategies can help the private sector — which has typically driven the provision of broadband services — plan their investment decisions.

- Establish a strong spectrum policy with the provision of clear, time-bound targets that looks at both licensed and unlicensed spectrum. Such policies must be backed by good spectrum management practices. The practice of setting exorbitant reserve prices and up-front fees for spectrum inhibits growth and causes delays in the rollout of services. Regulators will also need to set realistic spectrum licensing requirements and enforce obligations to preventing hoarding or under-utilisation of the scarce resource

- Expand connectivity opportunities beyond mobile. Mobile technologies have been instrumental in expanding internet access but they have limitations. Some of the most meaningful tasks such as applying for jobs and building websites are tedious without desktop access. Governments need to encourage a mix of technologies suited to the geographies of their countries. This could mean new models of fibre to the premises (FTTP) such as in high rise homes or offices in combination with other emerging broadband technologies such as community networks, wifi meshes, innovative wireline/wireless solutions, satellites and balloons. With incentives such as subsidies, communities could be encouraged to pursue affordable broadband access themselves, as Zenzeleni in South Africa and Rhizomatica in Latin America have done.

- Support better infrastructure provision, including infrastructure sharing and more efficient, reliable energy solutions. Governments must tackle bureaucratic bottlenecks limiting permitting by establishing a one-stop-shop or single window for processing permits. Multiple forms of taxes from municipal authorities for rights of way and the rising civil costs of rollout applies an undue financial burden on investment. Having an infrastructure sharing strategy in place can offer clear guidelines for sharing both passive (e.g. towers, cables) and active components of infrastructure at base stations, backhaul sites, landing stations and data centres.

- Resist the urge to tax end-user devices and data. The emerging trend of governments applying consumer taxes drives up the cost to connect, keeping people offline. Discriminatory or sector-specific taxes pose limitations to investment and increases consumer costs.

- Increase public access opportunities using new sustainable investment models such Public-Private Partnerships, Universal Service funds — which have been used in Malaysia for middle and last-mile broadband connections — and by funding free and subsidised WiFi in public spaces like hospitals, bus stops, libraries and schools. Strategies must target marginalised groups most likely to be offline such as women and those who live in rural communities.

- Prioritise content, digital literacy, adoption and other demand-side initiatives to stimulate broadband use. Government funding, tax incentives and subsidies can complement private sector and NGO funding to encourage people to be producers as well as consumers of content. To ensure people are able to use the internet in meaningful ways, we need policy interventions to drive digital literacy, such as updated school curricula and targeted local learning initiatives and awareness schemes.

For more updates on our work, follow us on Twitter at @a4a_internet and @Ellasarpong.

Leave a Reply